|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|

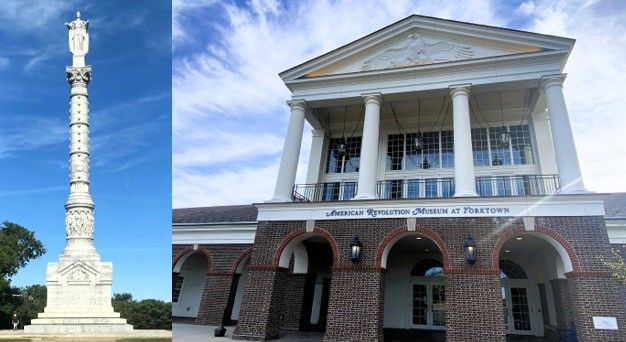

Virginia Yorktown Victory Monument and American Revolution Museum

Founded in 1691 as a tobacco port on the York River, Yorktown was a vital colonial trade hub before the war. It became the county seat of York County in 1696, and though small in size, it played a major role in early American commerce and governance. The town also played a role in the American Civil War, serving as a strategic port for both Union and Confederate forces depending on control. Yorktown is part of Virginia’s Historic Triangle, alongside Jamestown and Williamsburg and is part of the Colonial National Historical Park. Visitors to Yorktown are able to participate in walking tours, battlefield drives, and visit the American Revolution Museum and the Victory Monument. Situated in the Colonial National Historical Park, the Victory Monument stands on Historic Main Street Yorktown as a national symbol of unity, resilience, and international cooperation. It was erected in 1884 to commemorate the British surrender and the alliance between the U.S. and France. Authorised by Congress on October 29, 1781, just ten days after the British surrender by General Cornwallis, the monument was intended to honour the alliance between the United States and France and the victory that secured American independence. Despite this early resolution, construction was delayed for over a century due to political and financial reasons. Renewed interest during the Centennial of Yorktown in 1881 finally led to its completion in 1884. Designed by Architect Richard Morris Hunt, a prominent American architect known for his Beaux-Arts style. The original Sculpture was crowned by a figure of Liberty by John Quincy Adams Ward, but that was destroyed by lightning in 1942 and replaced in 1957 by a figure of Victory sculpted by Oskar J. W. Hansen. The monument is a granite column 84 feet in height adorned with emblems representing the Franco-American alliance and inscribed with a narrative of the surrender. It honours General George Washington; Count de Rochambeau (French land forces) and Count de Grasse (French naval forces). Until 1931, an enlisted Army soldier stood guard at the monument, emphasising its importance as a site of national memory. The Battle of Yorktown (September 28–October 19, 1781) was the final major engagement of the American Revolutionary War, culminating in a decisive Franco-American victory that forced the British to surrender. General George Washington led the Continental Army, supported by French General Rochambeau and Admiral de Grasse. British forces were commanded by General Charles Cornwallis. The Franco-American forces consisted of 19,800 troops and 29 French warships, while the British and German allies had only 8,000 troops. After years of attrition, Washington sought a decisive blow. Though New York was a tempting target, Rochambeau persuaded him to strike Cornwallis in Virginia. Cornwallis had fortified Yorktown, expecting reinforcements via sea, but Admiral de Grasse’s fleet blocked Chesapeake Bay, defeating the British Navy at the Battle of the Capes on September 5. The Marquis de Lafayette, a French aristocrat and military officer’s forces pinned Cornwallis from the west, while Washington and Rochambeau marched south from New York, completing a 450-mile trek in under six weeks. The siege began on September 28, 1781, with Franco-American forces encircling Yorktown. Artillery bombardments devastated British defences. On October 14, American and French troops captured key redoubts in a daring nighttime assault. With no escape and dwindling supplies, Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781. The surrender effectively ended major combat in the Revolutionary War, leading to peace negotiations and the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The battle symbolised international cooperation, with France’s land and naval forces playing a pivotal role. It also marked a turning point in global colonial dynamics, inspiring independence movements elsewhere. Nearby are the Battle and Surrender Field with the preserved siege lines and fortifications offering an insight into 18th-century military engineering. The Surrender Field is located just west of Yorktown and is the ceremonial site where British troops formally laid down their arms on October 19, 1781, following the Articles of Capitulation. On the day of the surrender, British troops marched out of Yorktown between two lines: the Continental Army on the right and the French Army on the left, forming a corridor of honour and humiliation. General Cornwallis claimed illness and did not attend. Instead, General Charles O’Hara attempted to surrender to French General Rochambeau, who deferred to Washington. Washington, refused to accept the sword from a subordinate, and directed O’Hara to General Benjamin Lincoln. Though the Treaty of Paris wouldn’t be signed until 1783, the Surrender marked the effective end of the war. The site is now part of Colonial National Historical Park, with interpretive signage and ceremonial reenactments that honour the moment’s gravity. Visitors are able to see the defences and redoubts from the conflict. Also to be seen is Moore House which was where the surrender negotiations occurred. The Articles of Capitulation were negotiated and drafted on October 18, 1781, at Moore House, which is where the formalising of the British surrender that ended major fighting in the American Revolutionary War took place. The Surrender Negotiations, occurred on October 17, 1781, when the British General Cornwallis requested a ceasefire. The next day, representatives from both sides met at Moore House to negotiate the surrender terms. The final Articles of Capitulation were signed on October 19. The house was chosen for its location, which was outside the line of siege fire, undamaged, and neutral. It offered a discreet setting for diplomacy while concealing the dire British situation in Yorktown. The house was built around 1725 on Temple Farm and was originally part of the York Plantation granted to Governor John Harvey in the 1630s. Augustine Moore, a merchant and landowner, acquired the estate in 1768. His family fled to Richmond during the siege; unaware their home would become a site of national importance. The house subsequently suffered damage during the Civil War and was restored by the National Park Service between 1931 and 1934, their first major restoration project. Moore House is part of Colonial National Historical Park, and while its interior is not open to the public, its exterior remains a powerful visual location for reenactments and historical interpretation. The American Revolution Museum at Yorktown officially opened in 2017, replacing the earlier Yorktown Victory Centre which opened in 1976 as part of the United States Bicentennial celebrations. In 2007, planning began for a major transformation to create a more comprehensive museum experience. The groundbreaking for the new museum occurred in 2013, with phased construction of the new building and outdoor living-history areas which, with the official opening occurring in March 2017. The new museum expanded both the indoor galleries and outdoor interpretive spaces including a recreated Continental Army encampment and 18th-century farm, offering a deeper and more immersive look at the Revolutionary era. The 22,000 square feet of permanent galleries within the museum showcase rare artifacts, dioramas, and interactive displays and includes over 1,300 artifacts. It includes a film “Liberty Fever” which sets the stage for the museum experience. The indoor galleries at the museum offer an immersive, artifact-rich journey through the Revolutionary era, blending traditional displays with cutting-edge multimedia and inclusive storytelling. The lobby contains a statue of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, a figure often associated with triumph in both war and civic achievement; this was chosen for its evocative condition, headless and armless, to reflect the fragility and complexity of victory. The statue’s origin is symbolic rather than archaeological as it was likely commissioned or selected by curators to complement the museum’s narrative strategy. The galleries are based on a theme or subject and are chronologically arranged, guiding visitors from the colonial unrest through the war and into the early republic. They contain artifacts - including weapons, uniforms, documents, and personal items – which are paired with interactive touchscreens, immersive soundscapes, and dramatic lighting to bring the Revolution to life. The museum emphasises diverse voices, including enslaved people, women, Native Americans, and ordinary citizens, offering a fuller picture of the Revolutionary experience. Personal stories and first-person accounts are woven throughout, making the galleries emotionally resonant and historically rich. The museum includes replicas of military equipment, such as a 24-pound French siege cannon and naval artillery, which serve both educational and symbolic functions. A highlight is the “Siege of Yorktown” 180-degree theatre, which uses surround visuals and sound to simulate the intensity of the final battle. Within the museum are featured a number of statues of the prominent people of the time of the revolution; the most famous being a mid-19th century plaster statue of George Washington by William James Hubard, modelled after Jean-Antoine Houdon’s iconic marble sculpture. Originally housed in the United States Capitol, the statue was later acquired by the museum to anchor its narrative of Revolutionary leadership. The statue was praised for its lifelike accuracy, based on direct measurements and a life mask taken at Mount Vernon in 1785. |

|

|

|

|

|||

All Photographs were taken by and are copyright of Ron Gatepain

| Site Map |